Note: This is a reprint of an article we originally published in October 2015.

Note: This is a reprint of an article we originally published in October 2015.

One of the provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) is to close the coverage gap in Part D Prescription Plans (PDPs). By 2020, PDP members (that’s you) will only pay 25% of the cost of both generics and name brand drugs while in the coverage gap. The key questions are what is the schedule for this reduction and how will that affect the premiums for the PDPs?

Name Brand Drugs

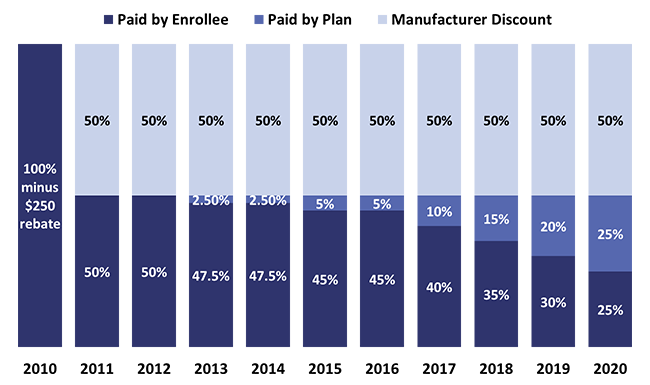

Starting in 2011, pharmaceutical companies were required to give members a 50% discount off the retail cost of brand name drugs when the member entered the coverage gap. The member paid the other 50%. In 2013 and 2014 the PDP paid 2.5% of the cost of brand name drugs reducing the members’ share to 47.5%. The manufacturers still contribute with their 50% discount. In 2015 and 2016 the PDP now pays 5% of the cost of brands while the member is in the coverage gap. The member’s share is reduced to 45%. (See chart #1 below)

The manufacturers’ discount remains at 50% as represented by the light blue. The dark blue represents the declining amount that the member pays. The medium blue represents the increasing share that the PDP pays. Thus, from 2017 to 2020 the PDP pays 5% more every year. Unless the plan receives an increased subsidy from Medicare, it has no other alternative then to raise the premium for the plan in order to raise more revenue to pay for their increasing share of the costs while a member is in the coverage gap.

Generics

As far as the PDP having to pay more for generics, the situation is very similar to what they will be required to do while their members are in the coverage gap. The only difference is that there is no manufacturers’ discount. We can assume that the margins for generics are much thinner, so there is little or no room for discounts.

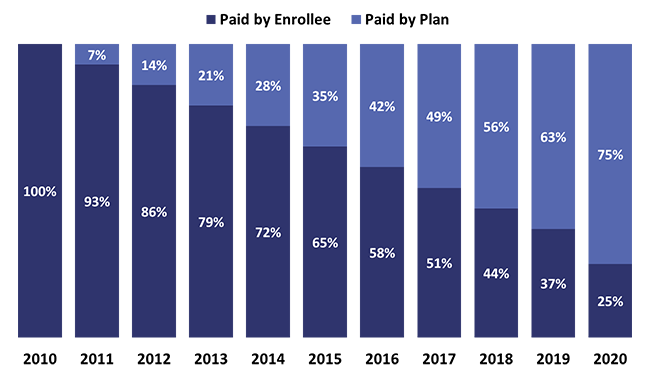

Starting in 2011, the plan paid 7% of the costs of generics when the member entered the gap. The member’s cost was reduced from 100% in 2011 to 93% in 2012. Every year until 2019 the PDP will pay an additional 7% and the member pays 7% less. In 2020 the member receives another 12% discount, reducing his/her share to just 25% of the cost of the generic drug. (See chart #2 below.)

The member’s share is represented by the dark blue, and the PDPs’ increasing share is represented by the medium blue. The declining share of the costs for the member certainly is advantageous for him/her, however, the PDP is being required to shoulder more of the costs.

Similar to paying more for brand name drugs, the increasing percent of the coverage for generics for the PDPs will add to their costs. This all puts pressure on premiums, pressure that pushes them higher.

Another factor that adds to premium increases is the increased costs for drugs. The PDP passes this cost along in higher copays or moving a drug from a “preferred” brand to a “non-preferred” brand. This change approximately doubles the copay for the member.

There is another strategy that the PDP uses to mitigate its increased costs. The PDP can drop a more expensive brand, or generic, as long as it has two drugs covering each therapeutic category. For example, most of the cholesterol drugs have gone generic. Many plans no longer cover Crestor, the only remaining name-brand statin drug, in their formulary. Since they cover lovastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin (Lipitor), they have the therapeutic category of cholesterol drugs covered. They do not have to cover the expensive brand, Crestor. Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in October of 2015. Since then, Crestor (Rosuvastatin) has gone generic.

In regards to premium increases, there is some good news. There is competition among the various insurance companies’ PDPs. We can assume that most of them would like to gain more market share. The competition has caused the copays for many inexpensive generics to go down. A couple of companies’ plans have either no copays or very small copays when the member orders his/her prescriptions through the companies’ mail order pharmacy.